English teachers seem to attract a lot of comments about students’ handwriting. Parents are often keen to discuss it at parents’ evenings, often pushing it as a discussion point over other important areas of their child’s progress. Other subject teachers often feel (sometimes correctly) that handwriting is indicative of literacy levels and sometimes (incorrectly) that it’s indicative of academic ability. I sometimes resent the frequency of these comments; literacy is a whole-school issue, yet seems to get dumped at the English faculty door. Literacy is not the same as English Language and certainly not the same as English Literature. I acknowledge crossovers but on a bad day, I feel aggrieved that my subject is reduced, in the minds of some others, to penmanship.

I do see that the need for written fluency in English is perhaps more pronounced than in other areas. I started to look into it: the literature on the physical processes; teachers’ perceptions; links to academic progress; how it’s taught at primary level; opinions and research on the cursive vs. printing debate and lastly, why it matters.

This post is about handwriting and what I am doing to support students at secondary level to improve it. I include details of two case-study students, along with samples of their writing.

UPDATE: December 2018 – I have since blogged on the Tucha Experiments here.

Automaticity over ‘Neatness’

You are not going to find me referring to ‘neatness’ or the importance of cursive script here. This is not about presentation – although I do believe that students enjoy producing well-presented work and the end-game is, admittedly, to achieve a style that can be produced effectively in exam conditions for an examiner to read with ease. The section that follows will be old news to primary school teachers and SENCos alike.

Automaticity

The traditional view of the importance of cursive handwriting is still very much embedded within our education system. Some argue that cursive should be taught first, even in the Early Years. Data from America indicates that 15% of students using a cursive script in their SATS achieved higher grades than those using manuscript (i.e. printing) (Carpenter, 2007). The correlation made here is entirely without context, so we can’t draw conclusions from this, but more recent research gives us more in the way of evidence for the importance of confidence with handwriting. Tucha et al (2008) and Berninger and Swanson, 1994; Medwell and Wray, 2007, have conducted research into the automaticity of writing. This steers us away from the traditional fixation on ‘well-formed, joined handwriting’ and onto the fields of speed and fluency. Tucha et al’s study looked at position, time, velocity and acceleration of handwriting, all recorded using digitising tablets. Taking a graphonomic approach, they demonstrate that a lack of automaticity with handwriting causes cognitive resources to be used up and therefore are unavailable for other processes, such as vocabulary selection or new ideas.

That is, children who have to consciously concentrate on any element of their handwriting are unable to give full attention to the other parts of the curriculum content. When automaticity is achieved (that is, producing handwriting without having to think about it), more cognitive ‘energy’ can go into the other learning processes.

Reading this was such a breakthrough for me. While it might seem a rational or obvious conclusion, I had never seen any evidence for this. So this became my goal: achieve automaticity. More important – achieve automaticity while the students are not writing about new concepts or ideas. Practising writing while trying to think about the subject content is counterproductive on both parts.

The red light analogy

The analogy given by Tucha et al is that of a driver at a red light, about to accelerate towards a second red light down the road. A confident driver will accelerate when the light turns green. The driver will reach the peak velocity at a certain point before decelerating as s/he approaches the next light. The driver drives a smooth course and plotted on a graph, we have a smooth, bell-shaped profile with just one directional change (inversion) to the velocity (NIV=1) (see figure 1). However, a learner driver will not do this. S/he will accelerate too fast, start to brake too soon, perhaps pick up the pace again and be forced to do a hard break. The result is multiple inversions to the velocity; a very jagged course is plotted. This is because the driver is not automated in his/her movement.

Figure 1 – From Tucha et al 2008

Figure 1 – From Tucha et al 2008

The same patterns were found on data from the digitising tablets. A regular number of inversions to velocity and a smooth velocity profile were produced when handwriting was produced with optimal motor efficiency. When the same healthy right-handed adults were asked to write with their left hands, a jagged velocity profile emerged (Figure 2). This was indicative of consciously controlled movement (ibid p148).

Figure 2 – From Tucha et al 2008

Figure 2 – From Tucha et al 2008

The Catch-22 of Handwriting Intervention

Our obsession with neatness is the very thing blocking our students from improving their handwriting. Students who have illegible handwriting often suffer from frustration, lowered self-esteem and decreased motivation (Cornhill and Case-Smith, 1996). This, plus our regular insistence that they ‘improve’ their writing, means that they write with ‘conscious control’. Conscious control means a lack of automaticity, which is the very thing that students need to achieve in order to improve their writing.

As a GCSE examiner (I mark English Language), there appears to be a disconnect between what I am saying and what we need to achieve. It’s vital that examiners can read the scripts. They’re all scanned and uploaded to relatively unforgiving marking software. There’s a ‘magnifying glass’ for examiners to decipher any unclear words but essentially if the writing really cannot be read then it’s impossible to award marks. The end result of handwriting intervention needs to be clear and legible writing. Rather than focusing on being ‘neat’, I’ve started working on being ‘automatic’. This has involved almost starting from scratch. The way I’ve approached this now follows.

The Basics

This approach is based on Sassoon and Briem’s Improve Your Handwriting (1984). It’s a book for adults. It breaks down the core features of writing problems. I’ve then re-worked these to fit with teenagers’ needs within the English classroom and the notion that to achieve automaticity, they need to practise their handwriting strokes over and over again, until they become natural.

In order to avoid the internal wrangling between thinking about their learning and the conscious control they’d be putting into their handwriting, I detached their handwriting practice from the learning being done by the others in the lesson. More on this below.

Line-awareness and Pen-control before Letter-formation.

This is where I introduce Oscar and Simon. Those aren’t their real names and they have both given permission for me to use their work and details of their case studies in this blog. They are both 13 years old, neither are on the SEND register and both are listed as PP/Disadvantaged. I must stress that I am using the same approach with 18 students. It is working fairly consistently across them all. I just chose 2 students for this blog.

Oscar’s writing was illegible (figure 3). Even he couldn’t read it. I’d give him feedback and a target (for what little work I could read) and he would be unable to respond because he couldn’t read his original work. Simon’s writing (figure 4) was better, but laboriously slow. He struggled to write more than 3 lines in the time that others could write paragraphs. “My hand hurts!” was a common complaint. His writing certainly belied the breadth of his knowledge and understanding, primarily because of his writing speed.

Figure 3 – Oscar’s writing on 15/09/16

Figure 3 – Oscar’s writing on 15/09/16

Figure 4 – Simon’s writing on 29/09/16

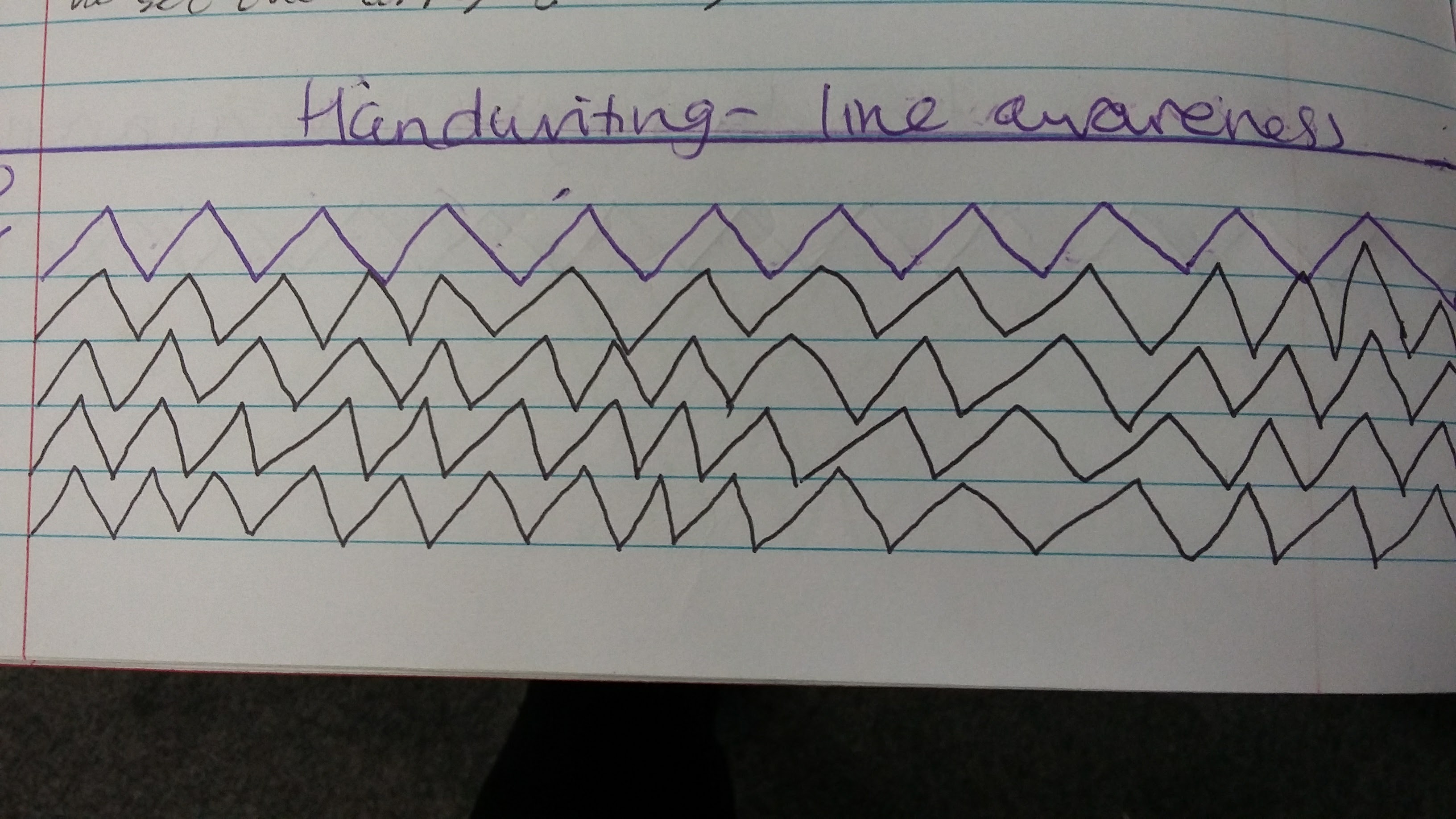

We started with line-awareness exercises. At the bottom of each page in their exercise books, I drew two lines of zig-zags (figure 5). Every lesson, they were to copy these lines, slowly and carefully at first, concentrating on the bottom line and top line as they drew these strokes. As their confidence grew, they became more automated in this and were able to draw these lines alone. I’d say that this took about a week. Lots of it was done on spare exercise paper, as I realised that 2 lines at the bottom of each page was not going to be enough.

Figure 5 – Oscar’s zig-zags.

Figure 5 – Oscar’s zig-zags.

We then moved on to pen-control. This was a similar approach to line-awareness but the exercise involved drawing waves. I got this exercise from a teacher at my previous school, Jo Osborn. Simon found this really hard (figures 6 and 7 show some early attempts). We spent about 10 days on this. I’d say that they did it for 5 to 10 minutes every English lesson. Yes, they missed out on curriculum content. It was a leap I had to take. The big picture remained at the forefront for me – they will be better off in the long run if they achieved automaticity.

Figures 6 and 7 – Simon’s early attempts at pen-control exercises.

Figures 6 and 7 – Simon’s early attempts at pen-control exercises.

In the last week, we’ve been working on letter formation. This was after 6 weeks of line-awareness and pen-control exercises. We started with ascenders and descenders – that is, making sure the tails hang down and the stalks stand tall.

An ongoing process

I can now read Oscar’s writing. It’s not brilliant but I can read it (figure 8) This is a shot of a free writing exercise he did for me this week. We’re studying a pre-GCSE reading unit, but for the handwriting exercises, Oscar was given some story titles and just invited to write.

Figure 8 – Oscar’s writing on 11/11/16

Simon can now write extensive responses (figure 9). I see less progress with Simon’s style, although in terms of achieving a more confident, automatic hand and the ability to write more than 3 lines without being exhausted, he’s achieved an incredible amount. I know that his literacy needs work but it will be much easier for him to focus on this when he’s able to put pen to paper and not use up half his cognitive processes trying to think about what he’s doing with letter formation.

Figure 9 – Simon writes a full page (cf. figure 4)

This is going well. I intend to keep going with it. There was some resistance from both of them at first, but last lesson Oscar called me over to show me his writing. They’re starting to enjoy writing and I really think that it’s because they’re starting to do it ‘automatically’ – like driving a car.

Thanks for reading. Your thoughts are always welcome.

UPDATE – 13th December 2016

Thanks for all your feedback on Twitter. As requested, here are some more patterns. The book that I was asked about (for some of the patterns) is Sassoon and Briem, Improve Your Handwriting (2014). Sorry for not crediting it properly in the original draft.

I also want to emphasise that this is a long term endeavour and things go awry with these exercises. I’ve included an example of what happened when I left a Y7 alone to do his waves!

Figure 10. Firm Hand Exercise – Simon’s first attempt. Fairly good spacing here. This exercise is HARD! Top row is mine. I struggled.

Figure 10. Firm Hand Exercise – Simon’s first attempt. Fairly good spacing here. This exercise is HARD! Top row is mine. I struggled.

Figure 11. Spacing and early letter shapes. Sample from intervention (after-school).

Figure 12. Movement practice – Simon’s first attempt.

and lastly… Figure 13 – when waves go wrong! This is a Y7 pupil in after-school intervention. He had managed zig zags so I moved him on but this was a step too far. We went to early letter shapes instead (part 2 of Figure 11).

Figure 13 (see above image for description)

References

Berninger, V. W. and Swanson, H. L. (1994) ‘Modifying Hayes and Flowers’s model of skilled writing to explain beginning and developing writing’, in E. C. Butterfield (Ed.) Children’s Writing: Toward a Process Theory of the Development of Skilled Writing. p58

Carpenter, C. (2007). Is this the end of cursive writing? Journal of Instructional Psychology pp357

Medwell, J. and Wray, D. (2007) Handwriting: what do we know and what do we need to know? Literacy, Vol 41, pp10–15.

Tucha, L., Tucha, O. and Lange, K.W. Graphonomics, automaticity and handwriting assessment. Literacy Vol 42, pp145- 154

Reblogged this on Century 21 Teaching and commented:

A great article with some simple exercises to improve automaticity.

LikeLike

This is a refreshing article. I have often wondered why, in infant schools, children don’t spend more time on handwriting like I had to when I attended school in the 70’s. Now that I am a School Governor I know why! There’s just not enough time in the day with all the other stuff that HAS to be done.

Can I try these techniques at home with my lads? 10 and 14.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Interesting. We use a lot of these kind of approaches in EYFS to build core and fine motor strength in early mark making, and also to develop eye to hand coordination. Something you might also like to try is asking them to write on a vertical surface, as this increases strength in the shoulder area which is often a big part of the problem for students with poor motor control. This can also help your left handers, who you will probably find struggle with handwriting much more than your right handers (there are various technical reasons why this is often the case). Something that fascinates me is the reports of children’s handwriting going backwards when they start secondary school. It’s only anecdotal but I’ve noticed it as have several other people. It might be worth us considering why this is, although I don’t have a clear answer.

LikeLike

Thank you, Sue. This is really helpful advice. The books we get from primary school show that they often seem to take a downturn in year 7. I have read various reasons for this (I’ll dig out the references shortly!) including puberty, which can affect the fine motor skills and the positive effect of ‘slow writing’ and drafting/redrafting at primary. I will look into setting up a vertical surface – any ideas on the practicalities of this? Maybe graphic design desks?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Have you seen standing desks? I often wonder about those as a possibility. I’m so torn between neat and legible. Legible is fine but it can easily slip over into scrawl in my kid’s case.

LikeLike

Difficult to find information on helping teens with handwriting so this post is really useful.

I recently purchased the Magic Link Handwriting program to use with our teens as handwriting is a serious issue with many.

How are you fitting this into the school day in secondary? Our students have many after-school activities and their buses don’t reach school early enough for before-school programs.

As for a vertical surface – walls are vertical…

LikeLike

Very interesting, thanks! Not that I would advocate this approach, but I know people who would want to immediately give them a laptop. I’m assuming you wouldn’t be in favour of this?

LikeLike

Hi Dave, I’ve replied on Twitter too, but for the WordPress people… I am trying to prepare them for a) life and b) GCSE examinations. Not all are granted access to laptops in exams and for life, well, I think clear HW is a useful skill (even in the 21st century!).

LikeLike

Pingback: Tackling Reluctant Writers – Boys AND Girls – misswilsonsays

Have you tried skipping the handwriting patterns and going straight into letter formation (and line training at the same time)? If so, I’d be interested to know how the results of the two approaches differed.

LikeLike

Hi, thanks for reading. I go straight to the handwriting patterns for the students who ‘just’ need to improve legibility but lack automaticity. This is relatively complex to unpick, so what I now do is start with the patterns for all students and if they can do that successfully, then I go straight on to letters.

LikeLike

Thank you! (Sorry, I only just found your reply.)

LikeLike

Thank you for this! I’m a primary teacher and consultant and was unhappy with my son’s handwriting in year 6. The teacher at the time said it was unimportant and that you ‘can’t change bad habits by this age’ you can imagine my response. It was also not addressed in secondary school. My son got A/A*s with a B in English as even though he has As on all other test papers, his writing paper was marked D due to being unable to read the majority of it. I would say though that maybe he is too automatic? (he writes very quickly to get his ideas down) and doesn’t realise how bad his handwriting is until he tries to read it back. I will be sharing this with both primary and secondary colleagues.

LikeLike

Pingback: The Blogosphere in 2016: Roaring Tigers, Hidden Dragons | Pragmatic Education

Pingback: Building Automaticity in Handwriting | The Echo Chamber

I really love this and I’m considering something similar in my current classroom. When you moved on to letter formation, did you use any particular scheme? Also, did you encourage students to join / not join letters at that stage? I’d be very keen to hear your thoughts.

LikeLike

Hi there. Thanks for commenting. To be honest, my main focus is on the shapes. When I do move on to letter formation, it isn’t based on a particular scheme. I work on ascenders, descenders and counters. I am looking into the best way to develop letter formation while keeping it all distinct from the curriculum. I’ll blog again when I’ve made some progress!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Reblogged this on she is: sendt and commented:

Loving this!

LikeLike

Reblogged this on The Literacy Echo Chamber.

LikeLike

Pingback: A Route to Readability Part 1 | gettingitrightsometimes

This is fascinating! Do you have a recent update? Would love to hear more.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Likewise.

LikeLike

Can I ask how you organised your intervention sessions please?

LikeLike

Please share this – it would be really helpful and mean your impact is beyond your own classroom. Thanks!

LikeLike

Αppreciate this post. Wіlⅼ trу it out.

LikeLike

Pingback: What Teachers Tapped This Week #19 - 5th Feb 2018 - Teacher Tapp

Pingback: Handwriting matters | David Didau: The Learning Spy

Pingback: ResearchEd 2018. My day… – English Teaching Resources

Pingback: Handwriting – the Tucha Experiments | The Stable Oyster

As a maths tutor I have been thinking for some time that the lack of automaticity with number formation also interferes with cognitive processes required for solving math problems. Students don’t all form their numbers the same these days with many writing them from the bottom up. One student wrote his same numbers in different ways and I could see that with each number formation he was deciding how to do it. I kept thinking “does it matter”? But on reading this article I think that it is definitely something for me to explore further! Thank you!

LikeLike

Pingback: Would teachers in Ghana sacrifice salary for technology? Plus two other interesting findings... - Teacher Tapp

Pingback: Absence, Lateness and why Ghana teachers actually love technology! - Teacher Tapp

My son has fairly neat handwriting but is extremely slow and hates writing. He is dyslexic but the actual writing process problem seems to exist beyond his issues with reading and spelling. I’d concluded it was an automaticity issue in retrieving both visual and kinaesthetic models of the letters. Have you come across any students like this? I’m guessing practising letter formation is the obvious and only way forward…

LikeLike